The challenges of archiving research data – the Living With Data experience

Home >

by Monika Fratczak

In August 2022, we published an open data archive of some of the survey, focus group and interview data that we collected on the Living With Data project. We received ‘Unleash Your Data and Software’ funding from The University of Sheffield to enable us to prepare and archive our data according to FAIR principles of findability, accessibility, interoperability and reusability. In this blogpost, Monika Fratczak shares the challenges we encountered in making our research data open.

We tried to follow best practice guidelines for data archiving, but sharing research data well is not easy. Balancing anonymisation with making data useful is complicated for several reasons. As well as meeting the highest technical standards and FAIR principles, archived datasets should also meet high ethical and legal standards, to protect research participants.

Considering marginalisation and inequality when marginalising data

Because researchers are increasingly encouraged to share research data to maximise their benefits for society, it is often assumed that researchers should explain why they do not share data. In contrast, Jesse Fox and others argue that researchers should be required to explain why they wish to share the data and why it is ethical to do so, to ensure that opening up research data does not result in harms for marginalised groups. This includes explaining what participants were told would happen to their data, including who would have access to the data, what efforts were made at de-identification, and the risks for marginalised groups. Fox et al (2021) propose that a data repository should give researchers control over who can access their data and for what purposes and that if data are shared openly, they should meet de-identification standards. We were guided by these principles in our own data archiving.

What to archive, and whether to embargo

We started by reviewing what our research participants had consented to, to ensure that we anonymised, archived and shared our research data in a way that was consistent with what they had agreed to and what we said we would do in our ethics approval application. We did not archive interview transcripts and documentation from our interviews with staff in our named case study organisations, because we did not have permission to do so and anyway, doing so might make these participants identifiable. We made other qualitative data, including transcripts of focus groups and interviews with other participants, available with restricted access. We placed a permanent embargo on these files because our participants consented to sharing their data with authorised researchers only. This means that people outside of the University of Sheffield must request access from us in order to view the data, and explain why they are interested in them. We decided to archive the quantitative datasets without embargo, as this is what survey respondents agreed to. However, as with the qualitative datasets, it was necessary to check whether any personal data were identifiable.

Anonymising research data

One of the most important and time-consuming tasks in archiving our datasets was anonymisation. The main purpose of anonymising research data is to prevent reidentification of study participants. Ideally, only small changes should be made to the data during anonymisation, to avoid redacting too much information. However, we agree with the Finnish Social Science Data Archive, that this is easier said than done. Below we describe some important decisions we made during the anonymisation process.

Initially, we made sure that all direct and strong indirect identifiers were removed, and that participants could not be identified in the transcripts. This included removing things like participants’ names, locations and workplaces. Other indirect identifiers such as age, ethnicity, gender, education or occupation were left in, because they were important for our analysis. Indirect identifiers alone are usually not sufficient to identify a research participant, but it is possible to do so if they are combined with other demographic data. We therefore reviewed the initial anonymisation of all transcripts to ensure this would not be possible, before archiving them on ORDA. As a result of this process, we removed some, but not all, indirect identifiers.

In terms of mitigating the risk of reidentification from our quantitative data, we decided not to make the data from survey free text fields open access, and some demographic information, including education, sex assigned at birth, number of adults/children under five in the household or age (upper and lower ranges) of individual respondents. Instead, we published aggregated versions of these data. In both datasets, we considered whether exceptional or unique information and special categories of personal data, including racial or ethnic origin, religion, health data or sexual orientation, needed to be anonymised. We recognised the sensitivity of these types of information and acknowledged the potential for this data to re-identify participants. In some cases we concluded that it did need to be anonymised, and in some cases we concluded that it didn’t. We removed information about participants’ criminal past and domestic violence, as we considered this information to be irrelevant with regard to our research and likely to compromise participants’ anonymity.

Archiving datasets, and making them findable, accessible and reusable

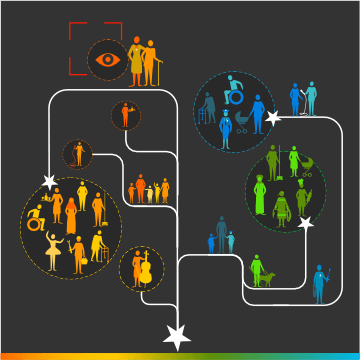

We prepared our dataset with appropriate metadata and documentation, assigned a CC BY 4.0 licence to it and uploaded the qualitative and quantitative data to ORDA. As well as archiving the data, we ensured the findability and accessibility (and therefore reusability) of our dataset by drawing attention to it on our Living With Data website in creative ways. We produced scripted animations of the visualisations that were used as elicitation tools in our fieldwork and we used quotes from transcripts to highlight the value of the archived data, linking to the ORDA archive. Finally, we shared this creative content through a carefully crafted campaign on our Living With Data Twitter account and team members’ personal accounts, accumulating more than 20,000 impressions in five days.

Archiving Living With Data research data well, in a way that was attentive to potential harm to marginalised or disadvantaged people and compliant with FAIR principles required lots of time, thought and learning. We think that, eventually, we did it well. The LWD data archive can be found here and the full reference for it is:

Kennedy, Helen; Oman, Susan; Ditchfield, Hannah; Taylor, Mark; Bates, Jo; Medina Perea, Itzelle; Fratczak, Monika (2022): Living With Data research. The University of Sheffield. Collection. doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.c.6122043

Fox, J., Pearce, K. E., Massanari, A. L., Riles, J. M., Szulc, Ł., Ranjit, Y. S., Trevisan, F., Soriano, C. R., Vitak, J., Arora, P., Ahn, S.J., Alper, M., Gambino, A., Gonzalez, C., Lynch, T., Williamson, L. D. and Gonzales, A. L. (2021) Open Science, Closed Doors? Countering Marginalization through an Agenda for Ethical, Inclusive Research in Communication, Journal of Communication, 71(5), pp. 764–784.